How a question about brain wiring led to better neural networks, and eventually a company mission.

In 2019, my collaborators and I at Carnegie Mellon published a paper about a phenomenon that was previously unheard of: that neural networks could learn better if we deliberately broke their wiring and never fixed it.

The idea was simple. Take a convolutional network, instead of a dense connection between its weights, initialize only a small subset of the connections randomly, then freeze that wiring permanently. Never change it during training, never change it during testing, and let the network learn to work with the hand it was dealt.

We called these architectures Permanent Random Connectome Networks (PRCNs). They outperformed networks with far more parameters, learned invariances that hand-designed architectures could not, and did it all with a fraction of the computational cost.

This post explains the idea, why it works, and why I believe the principles behind it matter more today than they did when we first published them.

I should say upfront that PRCNs were never just an engineering project. The question that was always top of mind throughout my career is a more fundamental one: what are the computational principles that make intelligence possible?

Biological brains are astonishing machines. They recognize objects in a glance, plan complex actions, and adapt to novel situations, all while running on roughly 20 watts. They didn't get there by brute force, but rather by discovering efficient principles: sparse coding, dynamic routing, hierarchical abstraction, selective invariance.

Modern deep learning has borrowed some of these ideas, but often only the surface-level ones. Weight sharing from neuroscience became convolution. Lateral inhibition became max pooling. But the deeper organizational principles, such as how the brain wires itself, how it allocates computation, and how it achieves robustness through apparent disorder, have largely been left on the table.

This work was one attempt to pick something up from that table. And the specific piece of neuroscience that inspired it is, I believe, fascinating.

If you looked at the neural wiring of two different people under a microscope, you would find completely different connectivity patterns at the local level. The precise pattern of who-connects-to-whom between nearby neurons in the visual cortex is different in your brain than in mine. And yet we both look at the same scene and see, to a remarkable degree, the same thing. Orientation selectivity, edge detection, object recognition: these shared visual experiences emerge reliably despite locally different, apparently random, neural wiring.

And here is the question that started it all: how is that possible?

This observation has profound implications. It means the brain's computational abilities don't depend on every connection being precisely specified. The principles of the architecture matter (the pooling, the hierarchy, the general structure) but the specific local wiring can be random, and the system still works. In some cases, the randomness may actually help by providing the diversity needed to learn robust representations from experience.

This was the observation that sparked PRCNs. We wanted to know: does the same principle hold in artificial networks? Can random local connectivity, fixed at initialization, produce better generalization than carefully structured wiring? And if so, what does that tell us about the relationship between structure and intelligence?

To test this, we needed a concrete problem where efficiency of learning really matters. The natural candidate was invariance.

Every useful perception system needs to be invariant to certain transformations. A face recognition system should recognize you whether you're photographed from the left or the right. A digit classifier should read a "7" whether it's rotated ten degrees or shifted a few pixels.

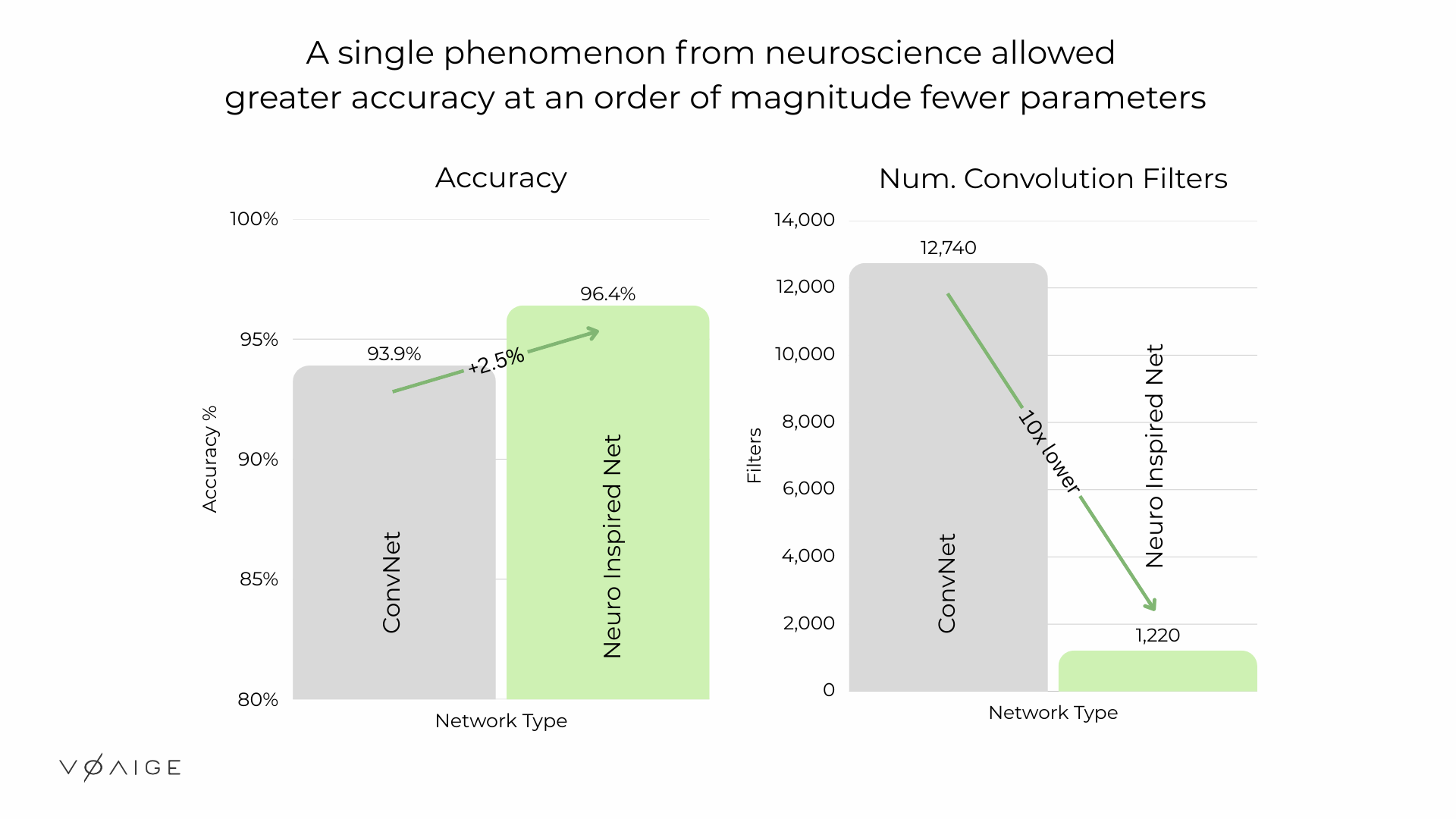

Standard convolutional networks can already learn many of these invariances from data, given enough capacity. The problem is that they do so inefficiently, requiring large numbers of filters and parameters to implicitly capture transformations that the architecture has no structural awareness of. Our claim was not that existing networks couldn't learn invariances, but that you could achieve the same or better results with an order of magnitude smaller network by incorporating ideas from neuroscience into the architecture itself.

Real-world data makes the efficiency problem worse. Objects deform, lighting shifts, and viewpoints change in ways that don't follow clean mathematical symmetries. The more varied the transformations, the more capacity a conventional network needs to absorb them all.

Biology doesn't work this way. The visual cortex doesn't scale up its neuron count every time it encounters a new kind of variation. It develops general-purpose invariances through experience, using architectures that are surprisingly unstructured at the local level.

The question we asked was: can a network learn invariances from the data itself far more efficiently, by borrowing organizational principles from the brain?

The core mechanism in PRCNs builds on a simple idea: if you have multiple feature detectors that each respond to slightly different versions of the same pattern (shifted, rotated, scaled), and you keep only the strongest response, the result is stable even when the input changes. The strongest response absorbs the variation. This is essentially what pooling does in a neural network, and it is the basic building block of robustness.

The type of robustness you get depends on which detector outputs you pool over. Pool over shifted versions and you get translation robustness. Pool over rotated versions and you get rotation robustness. But here's the tension: if you pool along one transformation axis only, you're robust to that one thing but fragile to everything else. If you pool over everything at once, you're robust to all variation, which sounds good until you realize you've also lost all ability to distinguish anything. Ignore too little and the system is fragile. Ignore too much and the system is effectively blind.

The key insight is to pool over a small but heterogeneous support that spans multiple transformation types at once. This gives you a feature that is partially robust to several transformations simultaneously, without collapsing into triviality. The critical design question then becomes: how do you choose this support?

Our answer was the simplest possible one, directly inspired by the neuroscience. Choose it at random, once, at initialization, and then never change it. Just as the brain appears to work with whatever local wiring it develops, PRCNs work with whatever random connectivity they're initialized with.

Imagine randomly assigning students to study groups and never letting them switch. Each group ends up with a different mix of strengths, and collectively they cover more ground than if you sorted them by ability. PRCNs work on a similar principle: random, permanent groupings force the network to develop diverse, complementary features rather than redundant ones.

Three properties work together to make this effective.

First, heterogeneity breaks degeneracy. Structured pooling is homogeneous, meaning every unit pools along the same transformation axis. Random pooling gives each unit a different support, producing a diverse bank of features with different robustness profiles. The downstream network can then select and combine these to construct whatever the task demands.

Second, random wiring induces efficient reuse. In a standard architecture, each filter's output feeds into exactly one downstream path. In a PRCN, a single high-quality activation can participate in multiple pooling units simultaneously, which means good features get reused rather than duplicated.

Third, permanence enables learning. Unlike dropout or stochastic pooling, which change connectivity at every forward pass, permanent random connectomes are fixed. The network can learn to exploit the specific wiring it has. The randomness is in the initialization, and after that, everything is deterministic.

We tested PRCNs on tasks specifically designed to demand invariance learning: recognizing digits under extreme rotations and translations, classifying objects across dozens of 3D viewpoints, and handling the complex augmentations that natural image datasets require.

The pattern was consistent. PRCNs matched or outperformed much larger conventional networks, in some cases using 3 times fewer parameters and 10 times fewer filters, without any pruning or compression. The performance advantage grew as transformations became more extreme, which is exactly what you'd expect if the architecture is genuinely learning invariances rather than memorizing training examples. When we removed the randomness as a control, performance dropped, confirming that the random wiring wasn't incidental and was doing real work.

For those interested in the full technical details, including the theoretical grounding and experimental results across multiple benchmarks, the paper is available at arxiv.org/abs/1911.05266.

PRCNs are one example of something I believe the field needs more of: taking a real phenomenon from neuroscience, understanding the computational principle behind it, and translating that principle into working AI systems.

The phenomenon here was locally random cortical wiring producing shared, robust perception. The principle was that heterogeneous, permanent connectivity can be a more efficient substrate for learning invariances than carefully ordered structure. The translation was PRCNs, which demonstrated this concretely in deep networks.

This was the kind of work that interested me while much of the field was focused on scaling: larger models, more data, longer training runs. The scaling effort has produced extraordinary results, and Rich Sutton's bitter lesson is not to be taken lightly. I have enormous respect for what it has achieved. But I also think there is a great deal left to learn from how biology solved the problem of intelligence under tight resource constraints. PRCNs were one proof point. The brain didn't evolve to be big, but it rather evolved to be clever about how it uses what it has.

If one observation from neuroscience led to 10x efficiency gains, how many other phenomena in the brain are we leaving on the table?

The neuroscience of intelligence is full of computational principles that have no counterpart yet in deep learning or AI. Dynamic gating, hierarchical prediction, adaptive resource allocation, efficient uncertainty collapse: these are not metaphors. They are mechanisms that biology discovered under severe resource constraints, and they remain largely untranslated.

Voaige was started to systematically explore this space. The goal is to identify the neuroscience phenomena that matter most for AI, understand the computational principles behind them, and build them into working systems. PRCNs were one chapter. We believe there are many more waiting to be written.

Dipan Pal is the founder of Voaige. He holds a PhD from Carnegie Mellon University, where his research focused on neuroscience-inspired architectures in deep learning, invariance, efficient computation.